Stella

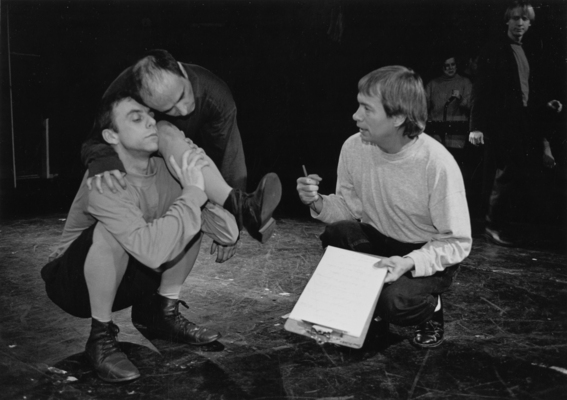

Jean-Pierre Perreault, artist

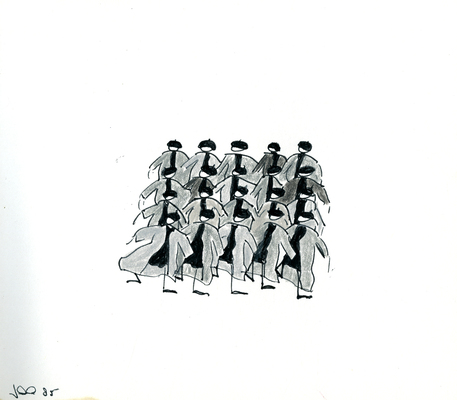

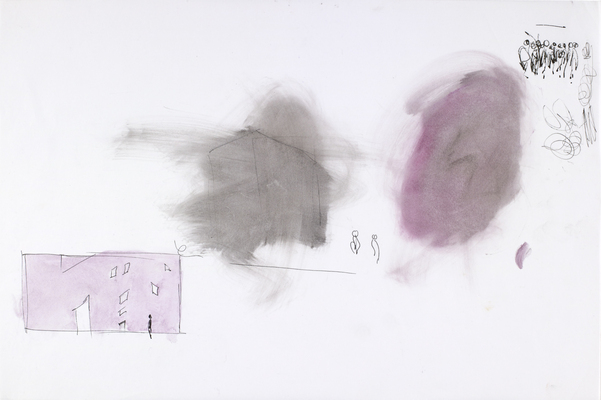

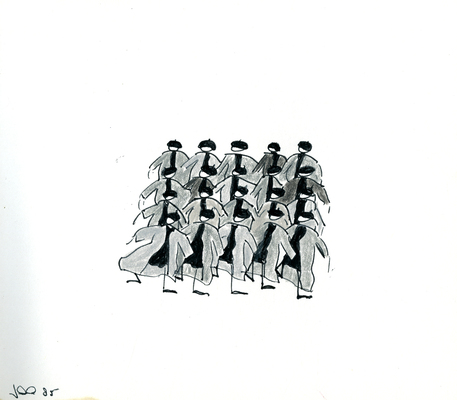

Select some drawings or photos showing dancers/characters. As a group, identify the main spatial elements in each of them: curved, straight or angular lines.

Identify the directions of these lines: *top/bottom – slanted – horizontal*.

What relationship do the bodies seem to have with verticality or gravity? Does it look like they are moving with or against gravity? Do their movements suggest hanging or falling? Are they balanced or off balance?

Form teams and ask each one to discreetly choose three drawings or photos. Each team then identifies the spatial elements in the selected images and draws the main lines on a piece of cardboard (two or three lines per image).

Take the exercise further: Use different colours to show the dominant qualities of the movement (yellow = light; green = strong, etc.).

Exploring the drawn shapes of the body

Each team’s sketches (lines) are given to another group. As soon as all the groups have a new series of sketches, they again *explore* the possibilities of the movement and the expressive qualities (lines and shapes) of the drawings.

Possiblities:

- Emphasize the main lines of the shape (awareness of the movement’s direction). Feel the direction taken by the different shapes and let the movement come. Explore the sensation of balance or instability, suspension or resistance against gravity.

- Explore the possibilities of movement in the kinesphere space.

- Follow the same lines, moving with resistance, as if the limbs were pulling an elastic material, or as if they were made of fragile glass, or were carrying heavy fabric, or as if they were weightless.

- Repeat the movements with different qualities.

- Move a single part of the shape (arm or leg) as if it were being moved by another person. Feel the weight of the body part and gravity at work.

Create a movement phrase

Determine the order of the sequence based on the three drawings or photos. Students can choose among the movements and possible ways to use the dynamics they have already explored (lightness, strength, resistance, impact movement, etc.) so that these dynamics are as closely aligned as possible with the original shape.

Connect the movements initiated by the three shapes into a continuous phrase.

Take the exercise further : Choose an evocative word (sensations – states – emotions) connected to weight (freedom, surrender, nonchalance, fatality, constraint, passion, etc.).

Return to your original drawing and touch it up by changing, if necessary, the thickness of the lines associated with the desired qualities (thick, thin, dotted lines). Colour the parts of the body that are most engaged.

Take the exercise further : Have each team present their composition to the class and ask the students to guess the drawings they chose. Each team can then exchange their drawings (sketches, not the original) with another team that will create their own interpretation of the lines and colours.

In the classroom…